By Jonathan McFadden

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of “Engineering in Reverse,” a three-part series in which we will explore the facets of reverse engineering, from process to product.

For J. Sanders and his crew of engineers at a Florida-based PMA company, enhancing the engine mount housing unit should have been simple. They had the original part in hand and just needed to figure out a way to duplicate and make it better. But there were problems.

To receive the Federal Aviation Administration’s coveted parts manufacturing approval (PMA), the tool would be subject to an intense level of scrutiny since it was an engine part, said Sanders, the company’s director of engineering. The company’s engineers were unable to answer the FAA’s barrage of questions. And because the original part came from a 1950s aircraft, it was saddled with a bevy of structural issues that made replicating it difficult. With no reprieve in sight, the engineers shelved the project for five years and, with it, the $40,000 worth of products they had already developed, Sanders said. Then, a year ago, Sanders’ company turned to AeroTech Engineering Consultants for an answer. Using the technology at its disposal, AeroTech helped the firm reverse engineer the part by scanning the OEM part and new products to find what components could be salvaged and improved. That prevented the company from trashing its products and starting from scratch, amounting up to $40,000 in savings.

“Our engineering department has been about five people. We have two, maybe three engineers on staff at a time,” Sanders said. “We try to take advantage of firms – such as (AeroTech). They’ve got the experience, the engineering know-how. It’s been a tremendous boost for us.” He adds: “We’ve got some tools; we’ve got specialty equipment but nothing to the magnitude (of AeroTech).

So, what is reverse engineering?

In the case of Sanders’ company, this is an example of reverse engineering at its finest. Simply, it’s the process of taking apart an object, figuring out how it works and then replicating it to create an identical part, or one that’s better.

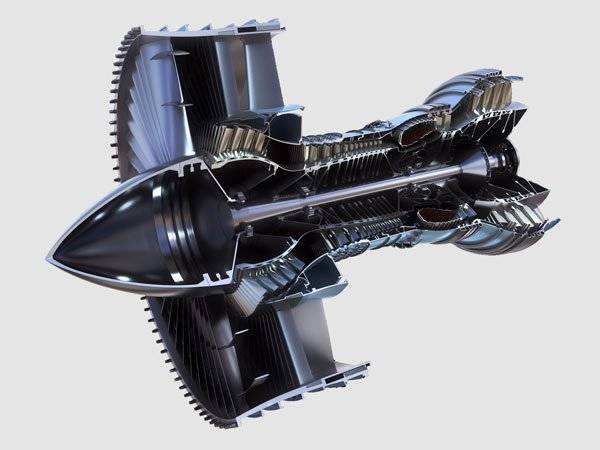

In the aerospace industry, companies use reverse engineering methods to develop parts that will achieve the Federal Aviation Administration’s PMA standards. That way, parts manufacturers and suppliers ensure they’re developing tools and components that meet federal standards before they take off into the sky. Reverse engineering is also useful for aviation operators and repair stations that need to create replacement parts during the repairing process.

For companies looking to remain relevant in the aviation space — and outlast the competition — utilizing reverse engineering techniques is paramount. The technology is so critical that researchers wrote in the Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing that is as much a key to the future of aerospace manufacturing as most computer-aided design models.

Why are we talking about reverse engineering?

In a day and age when spare parts are not easy to come by, reverse engineering could be the key to building and maintaining operable aircraft. Nowadays, reconstructing engineering and other important airplane parts is an often complicated and costly undertaking. The reasons are varied: Many casting molds no longer exist; the plane’s original manufacturer likely went out of business years earlier; and producing a brand new series of parts and components is financially impractical, according to Aviation Pros, an online resource for aviation news and industry information.

Reverse engineering makes it possible to precisely recreate parts and products, and very well could be responsible for reenergizing an industry that’s over a century old.

What do we do?

Since 2004, AeroTech Engineering Consultants has been reverse engineering parts for engines, propellers, aircraft and rotorcraft — all with the aim to help our clients manufacture the most reliable parts on the market.

We use the latest technology, such as whitelight scanning to mimic geometry, to completely reverse develop parts. This allows us to disassemble an existing object or product to see how it works so we can help parts suppliers and manufacturers enhance it. And we don’t just replicate geometry. We’re not interested in giving our customers a series of numbers and measurements so they can do the rest of the work themselves. Instead, we take the figures obtained from our scanning and measuring processes and help construct parts that are durable and trustworthy.

Our work has seen the development of more than 500 PMA tools and repair articles flying in the air today. We also have developed relationships with the FAA. We’re not afraid to speak with the executives making all the decisions, and we’re not afraid to advocate for our clients when it comes time for PMA certification.

For some of our clients, that’s resulted in peace of mind and measurable savings. Take Sanders and his crew, for example.

“One of the things a lot of people are hesitant to do is to sit down with the FAA. Anybody who’s worked with the FAA knows that the FAA is a bureaucracy that can tie up your time on the phone,” Sanders said. “(AeroTech) knows this business, knows what it takes. (It’s) able to talk to these guys and move products like no one I’ve ever seen.”